Unlike sharks and rays which have a well developed sense of smell, the cetaceans have virtually dispensed with olfaction as a method of gaining information about their environment.

Sight is moderately developed in some species, while the sense of touch is restricted to close contact.

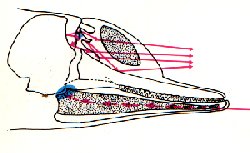

The cetacean emits sound waves which create echoes used to furnish information about the general topography of an aria, and to locate food.

Sounds are also used to give warning of enemies and to keep in contact with members of their own species.

echolocation

echolocation

This system resembles the asdic or sonar used by navies to locate submarines or to gain information about the sea bottom. Basically three broad groups of sound are used.

For information about the topography, low frequency clicks, which have great penetrating power, are used. For communication between members of the same species, somewhat higher frequency whistles are used, while location of food may depend on higher frequency clicks.

Coupled with these variations in frequency must go direction-finding.

Both ears receive information independently, thus giving a directional fix which is then interpreted by the brain.

In order that the cetacean ear could be used for the reception of underwater sounds, modification of the land mammalian pattern, unsuitable for hearing underwater, was necessary.

The middle ear has become much enlarged and is more rigid since the pressures involved are greater while the movements of the enclosed structures are much less.

The inner ear has also been modified to receive much higher frequencies since the same resolving ability requires frequencies four times higher in water than air.

When the normal air-adapted mammalian ears are placed in the water, they lose their direction-finding ability , since the vibration caused in the skull, by soundwaves, does not allow the animal to separate the reception of its two ears. In cetaceans, the ears are surrounded by air-filled cavities, which re-establish seperate function and allow directional interpretation by the brain.

Experiments have shown that as well as gaining a great deal of information about the size and position of underwater objects, including the topography, cetaceans can probably decipher their form and even their structure.

Such an ability is essential if food is to be identified.

The experiments show that the bottlenosed dolphin is able to distinguish between a piece of dead fish and an object of exactly the same shape, using sound alone.

It is assumed that cetaceans can defect differences in the reflection and absorption of soundwaves by different materials. the variety of sounds used by some cetaceans is legion.

The bottlenosed dolphin has been the subject of much study and in this species clicks, quacks and whistles have been described.

In addition, these animals may use both left and right nasal sacs independently, thus the right hole may whistle as the left clicks.